Materials Selection in GMP / Pharma / Medical Machines: When to Use Aluminum, Stainless Steel, Plastics, Seals, Coatings, etc.

Principles, Choices, and Best Practices

In designing machines for GMP, pharmaceutical, or medical use, the choice of materials of construction is absolutely critical. The materials must not only satisfy mechanical, chemical and operation al requirements, but must also comply with regulatory constraints, avoid contamination, ensure cleanability, and minimize extractables / leachables. Below is a detailed treatment of how to choose:

1. Aluminum: When (and when not) to use it

When to use aluminum:

- Non-product-contact structural parts (frames, guards, covers) where weight reduction is beneficial and chemical exposure is limited.

- Areas outside the wetted, hygienic / sterility-critical zones.

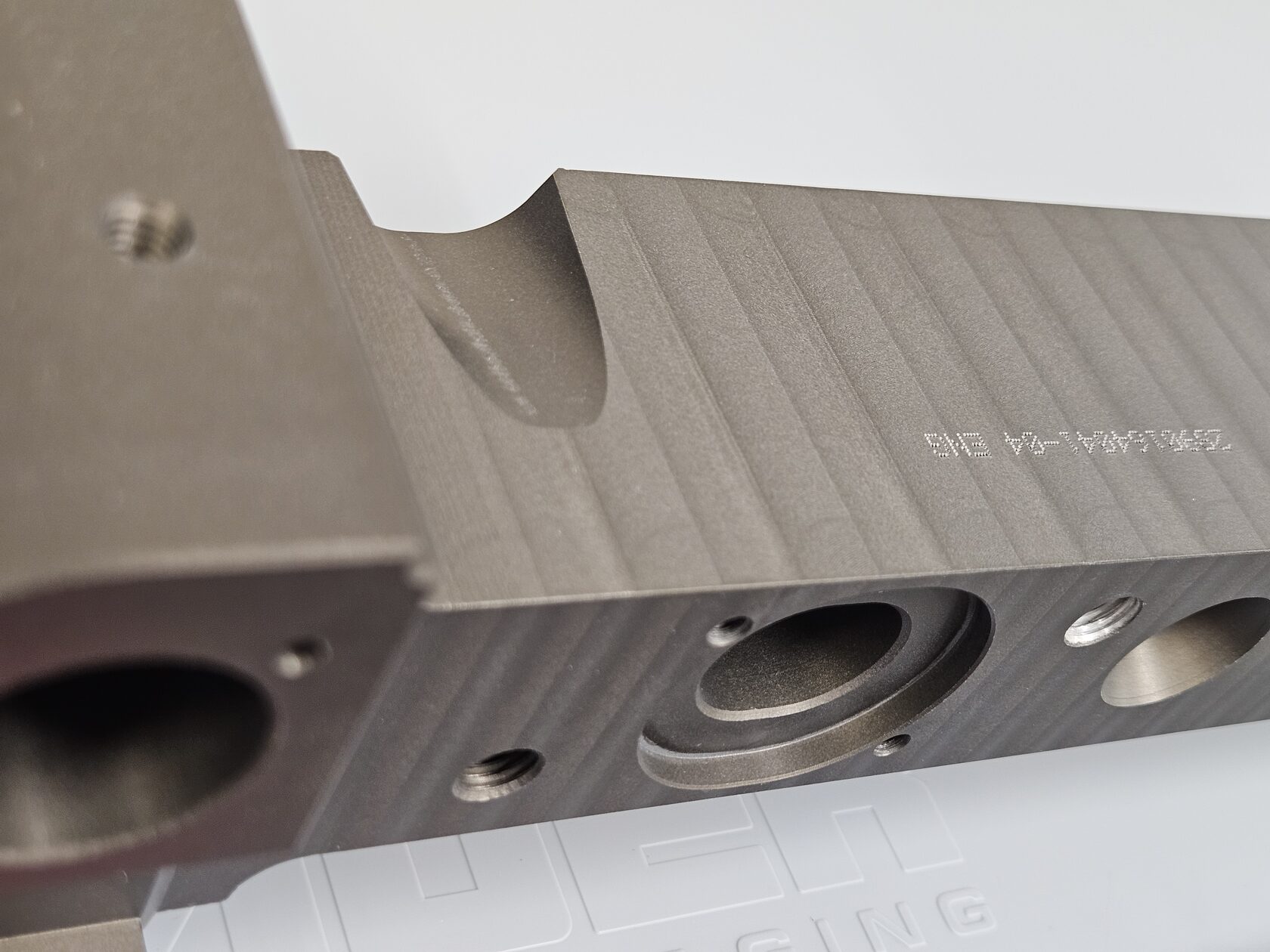

- Prototypes / lighter systems where cost, machinability, and agility matter more than high chemical resistance.

Which aluminum alloys:

- Recommended alloys: 6061, 6063, and 6082 (Al–Mg–Si series) are commonly used due to their good machinability, mechanical strength, and wide availability.

- Avoid using Alloy 7075, as its copper content makes it significantly more susceptible to corrosion in potentially aggressive environments.

- Always consider anodized or hard-anodized finishes; but the anodic oxide layer must be stable and non-leachable. So only very reliable partners must be used for such processes, providers capable to have under control their anodizing process. One of them, we use widely for Medical and Pharma use is the company MICRON COATINGS GROUP (Durox Srl) Aluminium anodizing. They provide us a perfect anodizing service with the following characteristics that we advice for these kind of applications:

- Hard natural anodizing

- Without pigments (to prevent their release when in contact with other elements)

- With sealed pores to avoid contamination.

- Beware of chloride-induced pitting if your cleaning / CIP / SIP uses chlorides or chlorine — aluminum is less tolerant than stainless steel in such environments.

Pitfalls / cautions:

- Galvanic corrosion when aluminum contacts stainless steel or other dissimilar metals in presence of electrolyte (water). Use insulating layers or isolate metals.

- Surface roughness must be controlled; micro-crevices might trap residues.

- Wear & scratching: aluminum is softer, so mechanical wear or abrasion can damage surfaces or expose raw metal. For this reason hard anodization should be always used.

- No official compendial standard for aluminum in pharmaceutical / GMP metal systems exists currently. The USP tried to develop a chapter for metal packaging, but it is still pending. gmp-compliance.org

- If used in contact with product, aggressive validation and extractables testing is mandatory.

In short: Aluminum is acceptable outside critical contact zones or in less aggressive environments.

Use it wisely, applying anodic protection and isolating it from stainless steel components.

The galvanic potential between these dissimilar metals can be highly risky and may lead to accelerated corrosion.

2. Stainless Steel and high-grade alloys for wetted components

This is the default choice for wetted or hygienic parts in pharmaceutical / medical machines.

Preferred grades

- 316L / 1.4404 - industry standard for pharma applications.

- 1.4435 (316L-mod.) or higher-end alloys (e.g., duplex, super-austenitic/6Mo, nickel-based) when exposed to harsh chemistries, high chloride/halide load, or tighter hygienic risk profiles.

- For parts under high stress or temperature, consider high-performance stainless or nickel alloys, but only with clear justification (risk, lifetime, or regulatory).

Critical clarification - stainless is not “non-corrodible”

Stainless steels resist corrosion thanks to a thin passive chromium-oxide film that requires oxygen to form and remain stable. In oxygen-depleted or stagnant conditions, especially in the presence of chlorides/halides and locally lowered pH, this film can break down, leading to localized attack:

- Crevice corrosion (the “danger zone”): occurs in gasket interfaces, clamp joints, threads, under deposits, or any tight geometry causing differential aeration. Inside the crevice, oxygen drops, chlorides concentrate, and the pH falls, creating an autocatalytic attack that is often irreversible once initiated.

- Pitting corrosion: similar mechanism in chloride media, initiated at inclusions or surface defects.

- These phenomena are characterized by Critical Crevice Temperature (CCT) and Critical Pitting Temperature (CPT); above these, even high-grade stainless can fail rapidly. Alloy selection (e.g., higher PREN) and surface/state control directly affect CCT/CPT.

Design and process mitigations

- Eliminate crevices: hygienic fittings, full-drain geometries, proper gasket compression, avoid dead legs and overlapping joints.

- Surface state: fine finishes (e.g., Ra ≤ 0.8 μm), electropolishing where appropriate, thorough passivation after fabrication.

- Process conditions: avoid stagnation, maintain flow and oxygenation where compatible, manage chloride load and cleaning chemistries, validate CIP/SIP so residues don’t create differential aeration cells.

- Materials strategy: where risk remains, step up from 316L/1.4404 to 1.4435, 254 SMO (1.4547), 904L (1.4539), duplex 2205 (1.4462), or Ni-Cr-Mo alloys (e.g., C-22) according to media, temperature, and required CCT/CPT margins.

Cleaning / CIP / CIP / SIP compatibility:

- The stainless design must resist repeated exposure to caustic, acid, peroxides, H₂O₂, sterilization cycles, etc.

- Surface finish must stay intact under abrasion, and no embedded surface irregularities should degrade over time.

Bottom line

Stainless steel is the right default for wetted parts, but its corrosion resistance depends on oxygen-supported passivity and geometry/process control. In low-oxygen, chloride-bearing, or acidic micro-environments, the material can become actively corroding with crevice corrosion being the primary mode to prevent by design and material choice.

Direct experience: we had a serious problem using standard physiological saline solution with AISI 316L volumetric pump, with DLC coating. We shall go deeper on this story in another article, because the matter is quite interesting 😊

A personal note on surface finish requirements

In the context of pharmaceutical and sanitary equipment engineering, it has become common practice, and is considered the current state of the art, to require that product-contact (or liquid-contact) surfaces have a surface roughness of Ra ≤ 0.8 µm as a typical accepted value.

(Sources: gmp-compliance.org, gmp-journal.com, pharmamachines.com)

For example, GMP-Journal states that “a generally accepted value for surface roughness (the smoothness) is 0.8 µm” for product-contact surfaces and highlights that sealing points and interfaces may represent critical zones.

Another reference (PharmaMachines / Hygienic Design) indicates that the “commonly adopted rule” is that product-contact surfaces should have a maximum roughness of Ra = 0.8 µm, with more stringent requirements (e.g., < 0.4 µm) in critical applications.

In a broader context, some sources suggest that for process-contact components a roughness between 0.4 and 1.5 µm may be acceptable, although microbial risk and cleaning difficulty increase as surface roughness rises.

The GMP-Compliance site also states that “for stainless steel, Ra ≤ 0.8 µm is the usual surface roughness requirement” for product-contact surfaces.

Other related guidelines (e.g., EHEDG, hygienic design standards) recommend that surfaces directly impacted by liquids or subject to residues should be smoothly finished and well-polished, minimizing deposits and avoiding cracks or crevices where cleaning becomes less effective.

So a reasoned interpretation could be as follows: when and where to apply Ra ≤ 0.8 µm

- Product-contact or liquid-contact surfaces (wet zones, liquid passages, seals, heat exchange areas, etc.) should have Ra ≤ 0.8 µm, preferably < 0.5 µm in critical zones.

- In non-contact areas (supports, structural frames, enclosures, covers, mechanical interfaces not exposed to product), higher roughness values (e.g., Ra 1.2 – 1.6 µm) can be tolerated, provided they do not affect flow, generate deposits, or compromise overall cleanability.

- It is essential that all direct-contact surfaces are homogeneous, free from deep scratches, cracks, or localized irregularities that could negate the nominal surface finish.

- The specification should also define the measurement method (e.g., profilometer, sampling length, measurement orientation) and inspection points (critical areas such as seals, gaskets, and internal surfaces of tubing).

- During qualification stages (FAT / IQ / OQ), the delivered surfaces should be verified and certified to comply with these specifications, including documented measurements and material certificates.

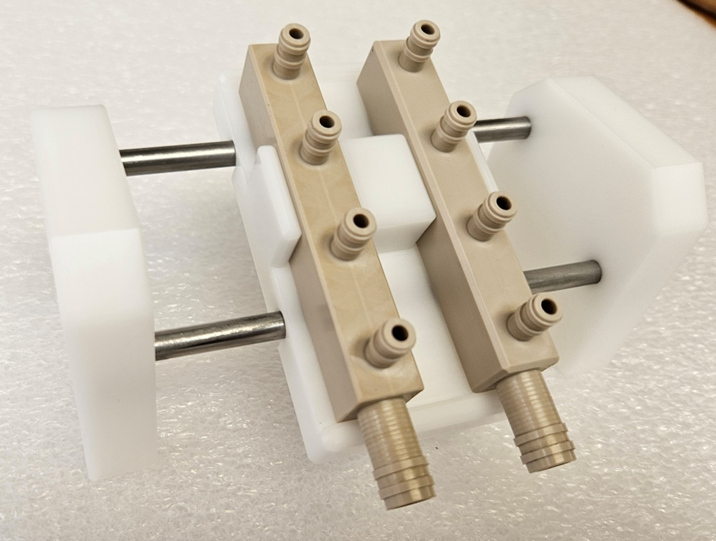

3. Plastics / Polymers: Use, selection, constraints

Polymers in pharmaceutical machinery

Polymers are widely used in pharmaceutical equipment for piping, tanks, sampling lines, sight glasses, protective shields, single-use assemblies, and various structural or functional components.

Selecting suitable plastic materials is often more complex than choosing metals, due to the need to control extractables and leachables, as well as concerns about adsorption, sterilization compatibility, and long-term stability.

For this reason, we aim to use only certified plastics, with great attention to their intended final application.

We have already discussed here: PEEK, POM and PTFE for CNC machining the use of engineering polymers in different areas, including medical applications - such as PEEK, POM, and PTFE - which are also suitable for CNC machining of critical parts.

Compatibility with the following factors can be crucial for proper material selection:

- Sterilization techniques (autoclaving, gamma, EtO, etc.)

- UVC light sensitivity and degradation

- Exposure to wet or humid environments

Key requirements:

- The material must not interact with the product (no chemical reaction, no leaching, minimal adsorption) gmp-compliance.org

- Must withstand cleaning / sterilization cycles (e.g. autoclaving, chemical cleaning).

- Must have an acceptable certificate or classification (e.g. USP <88>, USP Class VI). The stricter classes (Class VI) require biological testing (extractables, cytotoxicity). gmp-compliance.org

- For high-purity systems, the leachables / extractables behavior must be studied (worst-case extractables, leachables testing). gmp-compliance.org

- Must support qualification and verification (e.g. material certificates, test reports).

Common plastics in pharma / hygienic use:

- PTFE, PFA, FEP: excellent chemical resistance, inertness, wide temperature range; often used for linings, tubing.

- PVDF (polyvinylidene fluoride): good broad chemical resistance and mechanical properties.

- PE (HDPE), PP (polypropylene): used in less aggressive environments or non-critical zones.

- PEEK / polymers of higher performance used in niche cases (especially in medical device sector).

- Transparent plastics (e.g. polycarbonate, acrylic) used for sight glasses / shields, but must be carefully validated for chemical resistance and durability.

- Cyclic olefin polymers (COP, COC) in advanced pharmaceutical components (less common in heavy machinery).

Surface roughness and cleanliness:

- Plastic surfaces can often be molded with high polish from the mold, achieving roughness better than 0.8 µm. gmp-compliance.org

- Mechanical probing is risky (can scratch plastic), so non-contact methods (optical/white-light) are often used.

- Any adhesion, mold release agents, or additives in the plastic must be controlled and documented.

- CNC machining is a good way to create plastic parts. Finishing must be completed with a lot of care and for sure the PEEK is much more workable that other materials with this process.

Limitations & risks:

- Long-term creep / creep deformation under load, especially at elevated temperatures.

- Gas permeability or moisture ingress in some plastics may affect product stability.

- Thermal expansion often much higher than metals — careful mechanical design needed.

- Delamination, micro-cracks over time due to repeated sterilization / mechanical stress.

4. Seals, Gaskets, Elastomers

Seals are critical interfaces—if they fail, the process fails (leaks, contamination). The selection of sealing materials must consider both mechanical and chemical / regulatory aspects.

Material classes and their strengths:

- EPDM (Ethylene Propylene Diene Monomer) – good for aqueous, steam, many moderate chemistries, good temperature range (but limited in oils).

- FKM / Viton – strong chemical resistance, especially to oils, solvents, but costlier, may have more extractables.

- PTFE (or PTFE-encapsulated elastomers) – best inertness but low elasticity; often combined with a backup O-ring.

- FFKM (Perfluoroelastomer) – premium material with very wide chemical tolerance, used where highest resistance and low extractables are needed.

- Silicone – good temperature flexibility, but limited chemical resistance in aggressive solvents.

- HNBR (Hydrogenated NBR) – improved properties over NBR, better stability in more aggressive environments.

Regulatory / extractables considerations:

- Seals must often meet USP / USP <87> / <88> or equivalents (for biological compatibility).

- The sealing materials should have documented extractables / leachables studies, especially for contact with formulation fluids.

- In pharmaceutical / medical applications, you may require FDA-compliant elastomers (e.g., 21 CFR 177.x) for food / drug contact contexts. espint.com

Design / mechanical factors:

- Use compensating profiles (O-rings, quad-rings, dynamic seals) suited to pressure, movement, compression.

- Ensure surface finish and hardness of mating surfaces are within bounds so as not to damage softer seals.

- Avoid dead spaces, crevices, sharp edges around seal interfaces.

We shall try to prepare an exhaustive list of reliable suppliers for seals and gaskets, because we found crucial this point.

5. Surface Treatments, Coatings & Passivation

Even with great base materials, surface treatment is often necessary to enhance performance, cleanliness, inertness, or durability.

Common treatments:

- Electropolishing: smoothes micro-roughness, reduces micro-peaks, improves cleanability and corrosion resistance.

- Passivation (nitric / citric acid): removes free iron, improves corrosion resistance and oxide layer stability.

- PVD / DLC / ceramic coatings: sometimes used where wear resistance or inert barrier is needed, but must be stable, inert, and validated.

- Fluoropolymer linings / coatings: e.g. PFA or PTFE liners, for aggressive chemistries. Must adhere reliably and not crack under cycles.

Key cautions:

- The coating must not delaminate or crack under thermal, mechanical, or cleaning stresses.

- Coatings / treatments must be validated for extractables, durability under CIP/SIP, and must preserve the traceability / certification requirements.

- Avoid introducing new contaminants (e.g. from plating baths, chemicals) — ensure cleaning and documentation.

6. Summary Recommendations & Design Strategy

- Map functional zones: separate wetted/hygienic zones vs structural / support zones. Apply higher-grade materials only where needed.

- Start from product chemistry and process conditions: temperature, pH, solvents, cleaners. Use that to drive material choices.

- Specify surface finish, weld quality, passivation early in the design (not as an afterthought).

- Require material traceability and certificates (EN 10204 3.1 etc.) for all critical parts.

- Plan extractables / leachables studies for plastics, seals, coatings in contact with product.

- Avoid dissimilar metal contact without isolation to prevent galvanic corrosion.

- Design for maintainability and cleaning: no hidden crevices, smooth flow paths, avoid “nooks.”

- Validate over lifecycle: materials may degrade over time — perform accelerated aging, chemical exposure, sterilization cycles in your validation plan.

- Risk assessment: for each material choice, perform a risk analysis (ICH Q9 style) to evaluate potential contamination, leaching, mechanical failure, etc.

- Document everything: materials, treatments, certificates, validation data — GMP audits expect full traceability and justifications.

Bibliography & Key References

- ECA GMP Guidance — Revised Technical Guide for Metals and Alloys gmp-compliance.org

- GMP-Compliance.org — Requirements for Plastics in Pharmaceutical Equipment gmp-compliance.org

- GMP Journal — GMP-compliant Equipment Design: The GMP Equipment Design Guide gmp-journal.com

- GMP-Compliance.org — General requirements for Plastics in Pharmaceutical Engineering gmp-compliance.org

- FDA / 21 CFR, FDA guidance on material, containers and closures U.S. Food and Drug Administration+1

- FDA Guidance for Industry: Container Closure Systems U.S. Food and Drug Administration

- ESP / Food-industry seal guidance (FDA 21 CFR rubber seals) espint.com